We are commemorating two important events at UC Santa Cruz this year. It is the 50th anniversary of the first classes. It is also the 150th anniversary of the purchase of the property by Henry Cowell. Cowell’s entry into the annals of Santa Cruz history had long reaching effects. It set in motion a curious chain of events that, a century later, led to the creation of a great university. UCSC’s arrival, in turn, substantially changed Santa Cruz culturally, politically, and economically.

Although there were dozens of lime company owners in Santa Cruz County during the late nineteenth century, it is the name Cowell that is best known today. The name lives on through Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park, Cowell Beach, Cowell Street, and Cowell College, to name just a few.

So just who was Henry Cowell and why, in 1865, did he buy half interest in a Santa Cruz-based lime manufacturing business?

Uncovering the story of Henry Cowell and his family is not easy. Author Laurie MacDougall tackled the topic in a slim booklet published in 1989 by the S.H. Cowell Foundation. Archaeologist Pat Paramoure did some further research for a Cabrillo College term paper in 2007, and the authors of the Lime Kiln Legacies book included a short biography of him that same year. Although dead for over a century, Henry Cowell continues to perplex historians. Local newspapers heaped plenty of criticisms upon Cowell during his lifetime, despite his efforts to avoid the press. Furthermore, very little in the way of family or company papers have survived.

Nevertheless, new material continues to surface. This has been especially true the past few years with the digitizing of old newspapers and other publications. Literally hundreds of articles about Cowell have turned up that were previously almost impossible to access.

So how has Henry Cowell fared under renewed scrutiny? Was he really a crusty, hard-nosed businessman as some have written, or was he unfairly targeted for criticism precisely because of his success?

Very little is known of Cowell’s early life. He was born in 1819 on a farm in Wrentham, Massachusetts, the youngest of eleven children. During the Gold Rush, Cowell and an older brother, John, headed for California. There is no mention of them digging for gold. Instead, they sold goods to the miners, acting as agents for eastern merchants. Soon they developed a warehousing and hauling business. After a few years, John returned to the East.

Henry Cowell went East too (but only for a short time) to claim his bride, Harriet Carpenter. The couple returned to San Francisco and had six children, five of whom lived to adulthood.

In the late 1850s or early 1860s Cowell made a substantial loan to the lime-making firm of Davis and Jordan. Isaac Davis and A. P. Jordan had started making lime in Santa Cruz in 1853 where the Cowell Lime Works Historic District is today. They owned several thousand acres, had multiple lime kilns, a wharf, and schooners for hauling the lime to San Francisco. Jordan lived in Santa Cruz and managed operations here, while Davis lived in San Francisco where he ran the warehouse and sales office.

By early 1865, Jordan was dying from tuberculosis and decided to sell his half of the business. Cowell was the obvious buyer. “Mr. Jordan was very unwell at the time, and the papers were made out in haste for fear that Mr. Jordan would not live to sign the deeds,” said Cowell years later in court testimony. “I surrendered a note against Davis and Jordan for $22,000 and a little over, gave them $15,000 in cash, and my note for $25,000 to be paid in two years, and half of it to be paid in one year. . . .”

The move to the ranch near Santa Cruz must have been a dramatic change from the urban life of San Francisco. Santa Cruz had only around 1,500 or 2,000 people back then, while San Francisco—at 100,000—was the largest city in the state. While taking advantage of a business opportunity, Cowell (who grew up on a farm) may have thought that his children would benefit from the move to a rural community. There is no way to know this for sure, but we do know that his youngest son, Samuel Henry Cowell, developed a life-long love of animals and the outdoors.

“My family went down about the middle of July, and I joined them about the first of October, 1865,” Cowell explained. He immediately went to work overseeing the business. “I was cutting wood, hauling it, getting out rock and burning it into lime, making lime barrels, and shipping them.”

Jordan was well liked in Santa Cruz and worked for the betterment of the young town. He was generous— perhaps a little too generous—in making company resources available to the community. Cowell, on the other hand, was all business. Cowell sometimes fought against improvements for the community as a whole, such as new roads or railroads, because they would have benefited competing lime companies. During the late 1860s and 1870s these actions spawned a growing dislike and distrust of Henry Cowell among many Santa Cruzans.

Only a year or two after settling in Santa Cruz, Cowell tried to lay claim to the tidelands along the main beach. At that time, one could apply to the State for a grant of unclaimed marsh lands. Cowell said that he discovered that this land was unclaimed and that he was simply trying to acquire it to protect his wharf, which crossed over the intertidal sands. Santa Cruzans, however, saw it as a land grab that could also give Cowell control over the town’s only other wharf, which was used by competing lime companies and many other businesses. The Santa Cruz Sentinel vigorously attacked Cowell, eventually denouncing him as the “worst enemy Santa Cruz ever had.” (Sentinel, February 2, 1878)

Cowell responded to early criticisms in a letter discovered by archaeologist Pat Paramoure in the Watsonville Pajaronian of August 15, 1872. “The State of California offered the lands for sale and, through her officers, has received my money. . . . I did not wish to gain a newspaper notoriety, but when I am accused of one of the gravest of crimes—perjury, fraud, duplicity—justice demands that I should answer.”

Cowell seldom lashed out in writing, but he clearly despised the “irresponsible, rotten, mercenary press” in Santa Cruz. “An honest breath would kill them,” he wrote. “I neither care [for] nor fear you, and believe the most degraded criminal at San Quentin is as far above you in honesty, virtue, morality, charity and fair-dealing, as Heaven is above earth.” (Pajaronian, Aug. 15, 1872)

Cowell asserted that he was simply protecting his own business interests—namely the Cowell Wharf. If this were true, however, why did he try to lay claim to the entire waterfront, from the foot of Bay Street to the mouth of the San Lorenzo River, instead of just the tidelands under his wharf? We may never know. It took twenty years to settle the matter. In the end, the California Supreme Court ruled that the Santa Cruz beach did not meet the definition of worthless marsh land, and therefore the State could neither grant it to Cowell nor to anybody else.

In 1887 Henry Cowell’s construction of a fence nearly resulted in violence. Cowell had allowed a local company mining bituminous rock (used for road pavement) to haul the material across his land to shipping facilities in Santa Cruz. This went on for several years until Cowell decided to start his own bituminous rock business. Suddenly a fence went up blocking the route used by what was now a competitor. Employees of the competing plant decided to take matters into their own hands.

“At eleven o’clock Tuesday evening, [Robert] Majors was awaked, and on going to the front door, was confronted by seven men who were masked and carried rifles. . . . They intended to blow up Cowell’s house, where they supposed Cowell was staying, and also to burn up all the fences on Davis & Cowell’s lands.” (Sentinel, April 8, 1887) Fortunately, Majors, who was their superintendent, wanted no part of such violence and convinced the men to go home. The next day Cowell’s fence suddenly disappeared. (For more on the bituminous rock industry, see the Spring/Summer 2013 Lime Kiln Chronicles, available on our website.)

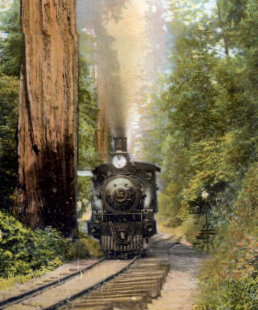

It seems Cowell was nearly always involved in some sort of legal entanglement. Historian Stan Stevens discovered this headline in the San Francisco Call of August 27, 1902: “Warrant for Arrest of Millionaire Cowell.” Cowell’s workmen had been felling redwoods near the Big Trees and some of the trees fell across the railroad tracks, delaying the U. S. mail. Cowell, explained that he had an agreement with the Southern Pacific that he would not be liable for damages resulting from the removal of trees adjacent to the railroad right-of-way. That wasn’t good enough, however, for H. P. Thrall, superintendent of the railway mail service. Thrall planned to “prosecute vigorously the case against Cowell” for twice delaying mail delivery by several hours. In court, however, the judge decided that the blocking of the tracks was not intentional and that Cowell had the right to cut timber on his property. (Sentinel, Sept. 4, 1902)

Although sometimes dubbed a “lime baron,” Henry Cowell had diverse business interests. These included raising cattle and other livestock, farming, buying and selling property and water rights, making loans, etc.

Cowell’s business interests even extended to Alaska. He sat on the Board of Directors of the North American Commercial Company, which in 1890 secured an exclusive 20-year lease from the federal government for the taking of fur seals on the islands of St. Paul and St. George. It was estimated that the company would be harvesting 100,000 pelts per year. (Daily Alta California, March 1, 1890)

Cowell had ranches scattered across much of northern and central California, from the Pacific shore to the Sierra foothills. According to early newspaper accounts, many were apparently acquired through foreclosures. “Henry Cowell was over in Monterey looking after his railroad mortgages, etc., and the press . . . found him as close-mouthed as an oyster. They should know that the only way to make our pet Henry communicative is to praise him gently, or to show him a scheme by which he can make money.”(Sentinel, Nov. 23, 1878) Everyone was very formal back then, so just the fact that the paper often called him by first name only, let alone a “pet,” was extremely disrespectful. “Henry Cowell is fencing his ranch near Half Moon Bay. Henry takes a mortgage and then gets a ranch. Salinas, Pescadero, and Half Moon Bay are loading him up.” (Sentinel, April 23, 1881)

Only a few acts of charity by Cowell have turned up in the old newspapers, but of course it is possible others went unpublicized. “We learn that Henry Cowell gave the other day to the Home for Incurables in San Francisco the sum of $1,000 to alleviate suffering.” (Sentinel, July 17, 1902) The Home of Incurables housed people who had diseases then determined to be incurable. His donation was the equivalent of roughly $27,000 today.

Cowell died in 1903. His surviving two daughters and two sons were much more generous than their father, again based on old newspapers. Ernest Cowell set up a scholarship fund at Santa Cruz High School (which is still in place), and sisters Helen and Isabelle frequently donated to hospitals and to relief funds for victims of various disasters. In 1906 Ernest aided the Santa Cruz Free Library, something his father had refused to do just four years earlier. Ultimately, nearly the entire Cowell family fortune went to charity. Samuel Henry Cowell (aka S. H. or Harry Cowell), who was the last surviving heir, established the S. H. Cowell Foundation shortly before he died in 1955.

It was from the Cowell Foundation that the University of California purchased the campus lands. The fact that the Cowell Ranch had just one owner (and one who was willing to sell) made the site especially appealing to the UC Regents.

Sometimes, the more we distance ourselves from people and events of the past, the more we learn about them and the better our perspective. So it is with the story of Henry Cowell. Certainly he was a powerful business tycoon, who knew what he wanted and took whatever legal measures he could to get it. But he was a complex individual. Perhaps someday, with more research, a comprehensive biography can be written. Until then, we will continue to share bits and pieces of his story as they come to light.