By Frank Perry

At least a dozen places in Santa Cruz County bear the Cowell name. Some are well known, such as Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park and Cowell College at UCSC. Others are lesser known, such as Cowell Mountain near Big Basin. A few were very well known historically, but have since sunk into obscurity. A good example is the Cowell Reservoir, so named because the site was purchased from Henry Cowell. In the 1890s and early 1900s, much of Santa Cruz's water supply came from this reservoir, so it was a name very familiar to the citizenry.

Readers who have visited the UC Santa Cruz Arboretum have probably walked right past the old reservoir site and did not even realize it. The area is now heavily vegetated, with a succulent garden and aroma garden growing on the earthen dam. Like so many things connected to the Cowell family in Santa Cruz, the reservoir has a fascinating albeit contro- versial past.

Its story begins in the late 1880s when Santa Cruzans voted to fund construction of a municipal water system. Prior to that, water for the town was supplied by two private companies.

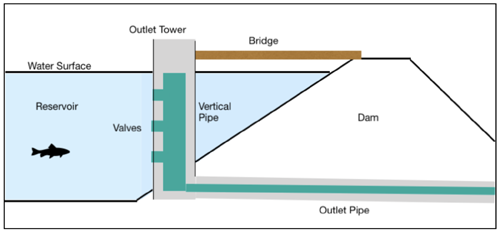

In 1889, the city bought the water rights to Laguna Creek on the North Coast. A contractor (Risdon Iron Works in San Francisco) was hired in December of 1889, but work on the dams and pipelines did not commence until early 1890. Workers built a dam on the creek to collect the water, laid several miles of pipeline to Santa Cruz, and built the Cowell Reservoir to store the water 450 feet above the town. The cleverly designed system operated on gravity, thereby avoiding the cost of water pumping machinery.

In March of 1890 the City formally accepted a deed from Henry Cowell conveying the reservoir site to the City for the price of $1,000. As part of the agreement, Cowell was entitled to free water from the reservoir for “lawn, garden, and domestic purposes” and to also use any “surplus or overflow” water. Cowell also had the right to stock the reservoir with trout—with all fishing privileges reserved for Cowell. The City agreed to fence the site and bury the pipes deep enough so that they would not be struck by plows.

It was not until October 18, 1890, that workers laid the last pipe and water began filling “the great reservoir above Cowell’s.” By November, the “pure waters” of Laguna Creek flowed through pipes on “every street.” The Santa Cruz Surf newspaper wrote romantically of the grand accomplishment, even publishing a poem in celebration of the event. It begins:

In the lengthening redwood shadows,

As the hours grow to close of day,

We gather around the workers

As the last joint of pipe they lay.

’Tis a link that binds together

The consummate work of years;

’Tis the crowning golden moment

That banishes all our fears.

Unfortunately, the Cowell Reservoir never fully lived up to expectations. It was supposed to hold 60 million gallons (about 221 acre feet), but never had more than 45 million gallons. The problem lay in the porous nature of the limerock on which the reservoir was located. The only lining to “seal” it was clay. At first the reduced capacity was not an issue, but as the town grew and the demand for water increased, the reservoir’s shortfalls became more worrisome. There were also claims that Cowell was using more than his rightful share of the water—a claim he denied.

In 1921, famed San Francisco city engineer Michael M. O’Shaughnessy (who developed the Hetch Hetchy water system for that city) was hired as a consultant to evaluate the Santa Cruz system and determine what studies were needed. By this time, the population of the town had grown to 14,000, almost three times the number when the reservoir was constructed. Liddell, Major’s, and Branciforte Creeks were also being tapped for water, though apparently not very efficiently. Much water was said to be lost at the sources.

O’Shaughnessy noted that many cities across the nation now used pumps rather than gravity systems and that Santa Cruz should investigate pumping more water out of the San Lorenzo River so the town would have additional water, especially in the summer. In 1924 the Bay Street Reservoir was constructed and a pipeline built so it could hold San Lorenzo River water. By the summer of 1932, a pumping plant at the San Lorenzoe River was pumping 5 million gallons per day of river water to the Bay Street Reservoir.

A study found that leakage at the Cowell Reservoir started occurring when the reservoir held more than 25,540,000 gallons. Talk of repairing and enlarging the reservoir continued on through the 1930s. One idea was to line it with bitumen (a natural mixture of tar and sand that was mined locally; see LKC Spring/Summer 2013) or to line it with cement. It was estimated that it could hold as much as 100 to 150 million gallons if enlarged and properly sealed.

Leakage wasn’t the only challenge. There were times when the water took on a peculiar taste and smell. Once it was supposedly because the water level was particularly high, flooding the grassy pasture up slope. More often the odd taste was blamed on algal blooms.

In 1932 a controversy erupted over the issuing of permits to the reservoir for fishing. Mayor Fred Swanton said that he should be able to issue passes, while city commissioner Alvin Weymouth said that only he had the right to give out passes. “I am responsible for the sanitary conditions at the reservoir and consider it my business to keep a careful watch on who goes there,” he said. It is not clear how the issue was resolved. Apparently by this time fishing rights were no longer restricted to the Cowells.

An article from 1934 said that “a few years ago” someone introduced crayfish into the reservoir. “In the seclusion of their quiet pond shut off from the general public by a high fence, the crustaceans found little to occupy their attention besides the pursuit of edibles and the raising of families. They attended to the latter so well that today their are literally millions. . . .” Interestingly, crayfish were harvested commercially there into the 1940s, with large quantities sold to local and San Francisco markets.

Despite more complaints of leakage, little was done to remedy the situation and much water continued to be lost. On one occasion, a hole 28 feet deep suddenly opened up in the bottom. The head of the water department speculated that the leaking water was helping feed the springs in the Westlake District. This was certainly possible, given the mysterious interconnections of the region’s limerock caves and fractures.

By 1947, the 57-year-old reservoir was losing a half million gallons per day. It was finally taken out of service the following year. Two large Army-surplus water tanks were installed nearby. Water from the North Coast was piped directly to the Bay Street reservoir, and water from Bay Street was then pumped into the tanks to serve the nearby Westlake neighborhood.

Rather than try to repair and reuse the Cowell facility, attention soon turned to building a new and much larger reservoir on Newell Creek near Ben Lomond. Completed in 1960, it was named Loch Lomond and is today the primary source of water for the City of Santa Cruz.

In the early 1960s, the Cowell Reservoir property became part of the new UCSC campus. In 1964 the campus arboretum was founded on land that included the old reservoir site.

Today the historic site can be seen by visitors to the arboretum. According to Brett Hall, long-time arboretum staff member, visitors are welcome to stroll around the edge of the site and view various plantings, including a collection of California conifers. As previously mentioned, the succulent and aroma gardens are located on the south slope of the dam, opposite Norrie’s Gift Shop. The site is rich in wildlife, including mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes, and many kinds of birds. Not long ago a weasel was sighted according to Brett—quite unusual. The reservoir still collects a small amount of water from winter rains, but this dries up in the summer. Nevertheless, it is home to the California Red-legged Frog, a threatened species. This species is also California’s official state amphibian.

The arboretum entrance is located off Empire Grade. Visit the website for hours and admission information.

https://arboretum.ucsc.edu/visit/index.html.

_____

This is the cover story that was featured in the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of our Lime Kiln Chronicles newsletter. To see the entire issue, please go here.